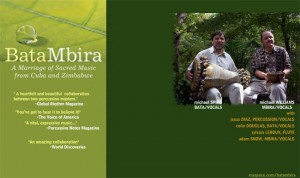

BataMbira

Michael Spiro is an internationally recognized percussionist, recording artist, and educator, known specifically for his work in the Latin music field. He has performed on hundreds of records, co-produced several instructional videos for Warner Bros. Publications (featuring such renowned artists as David Garibaldi, Changuito, Giovanni Hidalgo, and Ignacio Berroa), and produced seminal recordings in the Latin music genre, including Orquesta Batachanga, Grupo Bata-Ketu, and Grupo Ilu-Aña.

Mr. Spiro’s recording and performing credits include such diverse artists as David Byrne, Changuito, Ella Fitzgerald, David Garibaldi, Gilberto Gil, Giovanni Hidalgo, Bobby Hutcherson, Dr. John, Bobby McFerrin, Andy Narell, Eddie Palmieri, Carlos Santana, Clark Terry, McCoy Tyner and Charlie Watts. In addition, he has recorded soundtracks to such major motion pictures as “Soapdish,” “Henry and June,” “Eddie Macon’s Run,” and “Dragon-The Life of Bruce Lee,” and wrote several arrangements for the Tony Award winning Broadway show “BLAST!,” which was released on video by PBS in 2002.

He currently resides in San Francisco, California where he is an integral part of the Bay Area music scene. He records and produces with groups throughout the West Coast, and is touring world-wide with his percussion trio “Talking Drums,” which he co-leads with David Garibaldi and Jesus Diaz. In June of 1996, his own recording, “Bata-Ketu,” was released to international critical acclaim, and debuted on the stage in 2002 with a performance grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. That same year he performed with his own group, “Ara Meji,” at the 2002 Monterey Jazz Festival, where he received the Distinguished Achievement Award in Percussion. Most recently, in 2004 he received a Grammy nomination and a California Music Awards nomination for his work as both producer and artist on Mark Levine’s Latin-Jazz release, “Isla.”

B. Michael Williams is Professor of Music and Director of Percussion Studies at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Active as a performer and clinician in both symphonic and world music, Williams has performed with the Charlotte (NC) Symphony, Lansing (MI) Symphony, Brevard Music Center Festival Orchestra, and the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, and has appeared at four Percussive Arts Society International Conventions. He has written articles for Accent Magazine, South Carolina Musician, and Percussive Notes, and has made scholarly presentations on the music of John Cage and on African music at meetings of the College Music Society and Percussive Arts Society (PASIC).

Dr. Williams is Associate Editor (world percussion) for Percussive Notes magazine. A composer of innovative works for percussion, his “Four Solos for Frame Drums” was the first published composition for the medium. Additional works to his credit include “Three Shona Songs” and “Shona Celebration” for marimba ensemble, “Recital Suite for Djembe,” “Tiriba Kan” for solo djembe, “Bodhran Dance,” and “Another New Riq,” all published by HoneyRock Publications. His book, Learning Mbira: A Beginning…,also published by HoneyRock, utilizes a unique tablature notation for the Zimbabwean mbira dzavadzimu and has been acclaimed as an effective tutorial method for the instrument.

BataMbira Liner Notes

In the fall of 1998, I had the great pleasure (with the help and encouragement of my good friend and fellow percussionist, Beverly Botsford) of bringing Michael Spiro to Winthrop University, where I teach in South Carolina, for a series of lessons and masterclasses. Between sessions, Michael and I sat in my office sharing experiences and mutual interests. I told him of my interest in the Zimbabwean mbira dzavadzimu (the “mbira of the ancestors”) and we had a lively discussion about the cultural similarities between mbira and the Cuban bata drum. Both are sacred instruments with deep African roots. Both are used as spiritual media for contacting the ancestors (playing these instruments can be considered “praying with the hands”).

In the fall of 1998, I had the great pleasure (with the help and encouragement of my good friend and fellow percussionist, Beverly Botsford) of bringing Michael Spiro to Winthrop University, where I teach in South Carolina, for a series of lessons and masterclasses. Between sessions, Michael and I sat in my office sharing experiences and mutual interests. I told him of my interest in the Zimbabwean mbira dzavadzimu (the “mbira of the ancestors”) and we had a lively discussion about the cultural similarities between mbira and the Cuban bata drum. Both are sacred instruments with deep African roots. Both are used as spiritual media for contacting the ancestors (playing these instruments can be considered “praying with the hands”).

I took my mbira, closed my eyes, and began to play, singing in Shona: “Mushazoi sekerera nhamo ichauya…” (“Are you going to smile when the problem comes?”). When I finished, I opened my eyes to see a wide-eyed Michael Spiro about to leap across the desk toward me. “How’d you learn to do that?” he asked excitedly. I told him I’d had a couple of lessons here and there, but I had mostly learned on my own from various recordings. “Williams,” Spiro glared at me. “That’s impossible! But if it’s true, do you think it’s an accident that I’m here? Do you think you can just learn to play and sing like that in Rock Hill, South Carolina? When I closed my eyes, I heard an African singing! Many years ago, I was told by my elders that there is an African ancestor “walking” in my path, helping me to fulfill my destiny. I’m here to tell you there is an African in your path also. A American from South Carolina isn’t supposed to play and sing like that unless there is an African in his path! You’re my twin!”

We laughed at the irony of two Americans delving into the music of such far-removed cultures, and marveled at the similarities between the two African cultures that birthed these musical and cultural phenomena. Spiro joked that we should make a record together some day.

We kept in touch and Michael returned to Winthrop to teach occasionally. We continued to dream about making a record together, but we really didn’t know if the Cuban vocals accompanied only by drums, bells, and shekeres would be able to interface with the harmonic progressions of mbira music. One day, I received a package from Michael; a stack of CDs — maybe a hundred Cuban songs. “Find some that fit the mbira changes,” he said. Feeling a bit like I was looking for a needle in a haystack, I set to work. With about a dozen mbiras in various tunings surrounding me, I listened to the recordings and tried to play along — tune, after tune, after tune. I discovered a song that fit. Like a fisherman, I tossed my line in again. Soon, it began to feel as if the tunes were finding me as much as I was finding them. This was a lesson in synchronicity, and I was learning the value of stepping back and letting these ancient songs find each other. There was a bit of magic unfolding in the process.

As Michael and I began fashioning our raw materials into a musical Gestalt, we began to discover that the tunes we had chosen (or had they chosen us?) were interfacing on a number of levels. It seems that time and time again we were finding that the songs fit together semantically as well as musically. The project gradually took on a life of its own, and again we discovered the wisdom of getting out of the way and letting gravity take its course. In the process, a record took shape, our understanding of the incredible depth of this music increased, and a deep and lasting friendship was forged. To this day, we call each other “Twin.” It is with deep humility and respect that we offer this music in memory of our ancestors, and yours.

– Michael Williams

1. Butsu Mutandari/Iyesa – performed on a 15-key karimba (or kalimba), Butsu Mutandari is pleasurable dancing music. Butsu means “boot” or “shoe” in Shona, and refers to the gumboots worn by shangara dancers. In shangara, dancers tap the rhythms of drums with their feet. The Shona lyrics say “Look at my shoes! Watch me dance!”

The bata rhythm is Iyesa, and the Cuban songs are for Oshun, the goddess of female beauty and fresh water (specifically the river). She loves to dance to Iyesa, and she dances a specific step in this rhythm in which her feet “tap” the rhythm of the drums as well. The timbale solo, played by Jesus Diaz, adds to the secular, enjoyable nature of this particular tune.

2. Nhemamusasa/Afrekete Nhemamusasa is a hunting song, among the oldest songs in the mbira repertory. It means “temporary shelter,” and refers to shelters built by hunters from the branches of the musasa tree. Nhemamusasa encourages a sense of repose among the vicissitudes of life. The piece shifts to Kuzanga (literally “together in the village”), which means “living happily and free from fear.” Its lyrics say, “With whom will I stay while I am in the wilderness?” The implied answer is obvious, “Wherever you go, there you are.”

The opening sounds convey a sense of standing at the ocean, and the first drums heard are the Arara drums (from Benin) playing for Afrekete, the Arara goddess of the ocean. Afrekete is the equivalent to the Yoruba Yemaya. Kuzanga, with its 9/8 feel, is accompanied by the bata rhythm for Eggun (the ancestors), perhaps a reminder that the ancestors are always with us, ensuring that we can indeed live happily and free from fear.

3. Baya Wabaya – Literally meaning, “To spear, to spear,” Baya Wabaya is a song about a battle. The Shona language is rich in metaphorical connotations, and this aspect is compounded in song to the point that very different listeners may derive deeply personal meaning no matter what their circumstances might be. The battle referenced in this song could be a conflict between two people, or an inner battle; the slaying of one’s personal demons, or dealing with all manner of suffering. The essence of its sentiment is that a person in conflict is one whose world is turned upside down, and that conflict can be resolved and life returned to its natural course. The rhythmic accompaniment is once again for Oya (goddess of the cemetery), and is called Oyabiiku.

4. Nyamaropa/Mase – This piece begins with the mbira tune Mahororo. Because Mahororo is so closely related to Nyamaropa in terms of harmonic structure, these two landmark pieces fit very well together. Some consider Nyamaropa to be the mother of all mbira pieces; the first piece composed for the instrument and one from which all others are derived. The title literally means “meat and blood,” and refers to the scene following a successful hunt. Mahororo has several meanings that can all be connected somehow. One popular meaning has to do with flowing water, the sound of rain, or a river — perhaps a reference to the interlocking fingers of the left and right hands, creating a flowing pattern suggesting the flow of water. The Shona lyrics for Nyamaropa are especially meaningful, saying, “Are you going to smile when the problem comes?” Problems can be disguised opportunities. An additional Shona line says, “Hammer the arrow in deep,” referring to the metaphorical nature of the song as if to say, “Press the point! Understand the meaning of this metaphor and apply it to your life.”

The Cuban songs are again for Oshun, goddess of the river, and the auxiliary percussion at the beginning is reminiscent of the river and the forest. Oshun likes shekeres because all gourds (squashes, calabashes) are sacred to her. The drum rhythms are from the Arara tradition from the region just west of Nigeria known as Benin, where Oshun is known as “Mase.” The drumming is very different from bata, as there are four drums played with sticks, with the lead drum using one stick and one hand. The rhythm changes to the bata, playing the Ibanloke toque that accompanies many songs to Oshun. The Cuban songs are in praise to Oshun and the “crown” that she wears as the queen of beauty and all things gold and shiny.

5. Shumba/Oya – Shumba means “lion.” According to Chartwell Dutiro, “The mbira player is the interface between the spirits and the living people. In Shumba, I am singing to my totem ancestors. I am asking what we can do to make the spirits happy so they will protect us, and I am talking to the people, asking them to join me by dancing and ululating in praise of our ancestors.” The Shona lyrics ask the spirits why they are disappointed and do not come. The refrain, “shumba inonhuwa sora,” means “lion, you who cast a smell of grass as you pass,” as if to say, “We know you are among us. Why do you not show yourself?”

The Cuban vocals are sung to Oya, asking her to come and show herself. As the guardian of the cemetery, she also invokes the spirits of the ancestors. Almost all songs to Oya praise her power and strength so that she and the ancestors will protect us. In this case, the two cultures are synchronized. The rhythmic style of this piece is known as Bembe, with an added Iya from the bata battery for rhythmic interest.

6. Kariga Mombe/Obakoso – Kariga Mombe means “taking the bull by the horns,” or “one who can throw a bull to the ground.” Another generic translation is “undefeatable.” It is a song to encourage the strength to do what must be done. The Cuban songs are for Chango, a warrior who is undefeatable and always does what must be done, in war to defend his people, and in peace to give them strength in their personal lives. The songs begin with a very well known “road” (sequence) to Chango, accompanied by a rhythm known as Iyamase, shifting to ChaChaElekefum. Just as the Iya was added to the Bembe rhythms in Shumba, here the lead caja from Bembe is added to the bata battery for strength and excitement.

7. Hangaiwa – According to Chartwell Dutiro, “This song combines two classic musical styles – payinera guitar and jerusarema rhythm. Payinera is a style of guitar that was played by lone guitarists busking on trains and in beer halls. Payinera came to Zimbabwe with migrant workers from South Africa. Jerusarema is typical Zimbabwe rhythm from Murehwa. The lyrics describe the enduring love of the pigeon dove: ‘The pigeons will die in the nest together.'”

The rhythm begins with bongo and triangle before shifting to the bata toque Oyokota for Babalu Aye (the god of disease), and then to the third road (section) of Osain (the god of plant life) played here on congas for extra energy and drive. In addition, both the Fula and Bansuri flutes are included for added color.

8. Nyamamusango/Chango – Literally meaning “meat in the forest,” the Shona lyrics encourage the following of one’s dream. They say, “Look, I have been stabbed,” a reference to suffering of some kind. The song’s refrain says, “But there is plentiful meat in the forest.” The line “chinzvenga mutsvairo” (“broom dodger”) refers to a man who hangs around the house “dodging the broom” rather than doing something more productive. The song encourages such a person to go out and pursue his destiny, rather than sitting around waiting for it.

The Cuban vocals begin with one of the “rezos” (rubato sung prayers) for Oya, the only female warrior, goddess of wind and storms and guardian of the cemetery, before progressing to her rhythm known as Tui-Tui, where she dances her most ferocious and powerful steps. With the return of the mbira, the rhythm shifts to Oferere for Oya’s mate Chango (also a warrior), who is the god of thunder and lightening and male virility. The rhythm shifts yet again to Yongo, a generic rhythm to all orishas, with Cuban vocals in praise of Chango, asking him to appear so the people can interact with him.