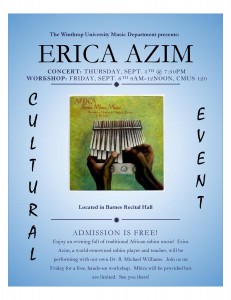

Erica Azim Performance and Workshop @ Winthrop University

Winthrop University will host Erica Azim September 5-6 for a concert and intensive workshop! Erica was among the first Americans to study mbira in Zimbabwe in the early 1970s (when the country was still called Rhodesia).

Thursday, September 5, 2013 – Concert, Traditional Shona Mbira Music of Zimbabwe – Barnes Recital Hall, 7:30 pm, admission FREE.

Friday, September 6, 2013 – Workshop, covering multiple aspects of Shona mbira music and culture – CMUS 120, 9:00 am – 12:00 pm, admission FREE. All welcome!

These are approved GLOBAL events.

Erica’s website:

Facebook Event:

https://www.facebook.com/events/367970806666049/

Erica Azim is a Californian who fell in love with Shona mbira music when she first heard it at the age of 16. After studying Shona music with Dumisani Maraire at the University of Washington for two years, she decided she had to learn to play the ancient Shona mbira played in ceremonies. She began to learn the instrument by ear, using taped mbira 45’s and an mbira borrowed from a professor’s shelf. Leaving her studies, Erica worked singlemindedly to save money for the journey to the opposite side of the earth.

In 1974, Erica became one of the first non-Zimbabweans to study the mbira in Zimbabwe with traditional masters of the instrument. At that time, Zimbabwe was racist Rhodesia in the throes of a liberation war. Touched by the arrival of a young white woman who respected ancient Shona tradition — a stark contrast with the white government that reviled it — musicians extended a warm welcome.

Although banned by the racist Rhodesian government from visiting the rural areas which are the home of mbira tradition, Erica easily found many mbira teachers in the capital city of Harare (then Salisbury). After a first mbira lesson with a stranger on a train, Erica studied seriously with Ambuya Beauler Dyoko, Cosmas Magaya, Mondrek Muchena, Ephat Mujuru, and others. By studying with many teachers, Erica was able to develop her own personal mbira style. She later returned to Zimbabwe and studied with additional teachers, including Irene Chigamba, Tute Chigamba, Chris Mhlanga, Fradreck Mujuru, Newton Gwara, Forward Kwenda, Luken Pasipamire, Sam Mujuru, Fungai Mujuru, Leonard Chiyanike, Patience Chaitezvi, Endiby Makope, Gift Rushambwa, and Renold and Caution Shonhai. Erica is known in Zimbabwe as a gwenyambira – a skilled performer qualified to play at traditional ceremonies.

In 1997, Erica Azim toured the U.S. with Forward Kwenda, teaching and performing. In 1998, she performed in the U.S. and Canada with Cosmas Magaya. In 2000, Erica performed at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC with Forward Kwenda, and they toured together in 2000, 2001 and 2002. She performed with Ambuya Beauler Dyoko during 2000 and 2001, Fradreck Mujuru in 2003, Fradreck and Fungai Mujuru in 2004, Irene Chigamba in 2006 and 2007, Vakaranga Venharetare in 2008, Patience Chaitezvi in 2009, Renold & Caution Shonhai in 2010, Caution Shonhai in 2011, and Leonard Chiyanike in 2012. Erica also performs solo mbira around the world.

Erica is particularly adept at making mbira music accessible to American audiences and mbira students. She currently teaches regional mbira workshop groups throughout the U.S. and Canada, and internationally-attended mbira camps at her home in Berkeley, California; Hawaii; and Argentina. She wrote the article On Teaching Americans to Play Mbira Like Zimbabweans for the Journal of African Music.

Erica Azim was responsible for the formation of the non-profit organization MBIRA, and directs its day-to-day operation, supporting over 235 traditional musicians and instrument makers in Zimbabwe.

Recent Comments